Overview of Plea Bargaining in Drug Cases

Plea Bargaining is a legal process in which the defendant in a criminal case agrees to plead guilty to a lesser charge or reduced sentence in exchange for a concession from the prosecution. This process is wholly acceptable and recognized in the Philippines as a means to expedite the resolution of criminal cases and manage court dockets more efficiently. As a way of disposing criminal charges by agreement of the parties, plea bargaining is considered “important”, “essential”, “highly desirable”, and “legitimate component" of the administration of justice (Estipona Jr. vs. Lobrigo).

THE ESTIPONA LANDMARK DECISION AND THE MONTIERRO GUIDELINES

Plea bargaining in drug cases was expressly prohibited under Section 23 of R.A. 9165 or the Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002. It wasn’t until in 2017, where the Supreme Court, in Estipona Jr. vs Hon. Lobrigo (G.R. 226679, August 15, 2017) struck down Section 23 as unconstitutional on the ground that plea bargaining is, for all intents and purposes, a procedural matter and, therefore, falls within the exclusive ambit of the Supreme Court’s rule making power under Section 5(5), Article VIII of the 1987 Constitution. In effect, the Estipona Decision empowers trial courts to hear and rule on plea bargaining proposals in drug cases.

Following this legal milestone, the Supreme Court found it prudent to issue A.M. No. 18-03-16-SC, a plea bargaining framework that laid down the acceptable pleas to drug offenses.

Plea bargaining continues to evolve and integrate into drug cases in the form of guidelines embedded by the Supreme Court in recent jurisprudence. In the case of People vs. Montierro (G.R. No. 254564, July 26, 2022), the Court provided the following guidelines (the “Montierro Guidelines”) to be observed by the defense, prosecutor, and the trial court whenever they plea bargain in drugs cases:

1. Offers for plea bargaining must be initiated in writing by way of a formal written motion filed by the accused in court.

2. The lesser offense which the accused proposes to plead guilty to must necessarily be included in the offense charged.

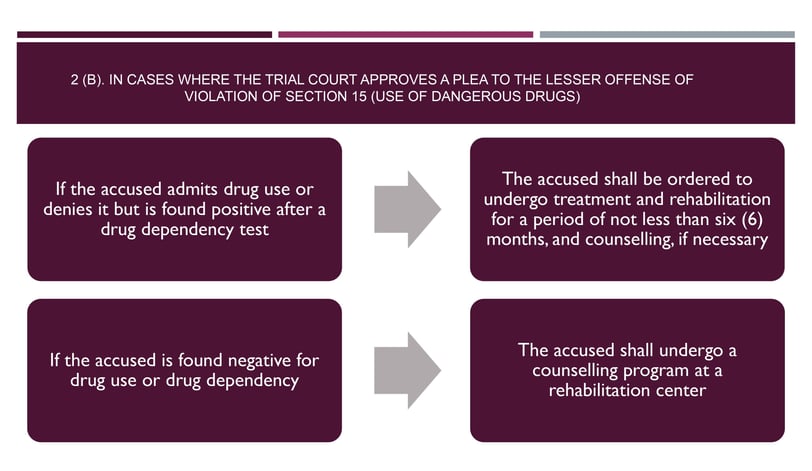

3. Upon receipt of the proposal for plea bargaining that is compliant with the provisions of the Plea Bargaining Framework in Drugs Cases, the judge shall order that a drug dependency assessment be administered. If the accused admits drug use, or denies it but is found positive after a drug dependency test, then he/she shall undergo treatment and rehabilitation for a period of not less than six (6) months. Said period shall be credited to his/her penalty and the period of his/her after-care and follow-up program if the penalty is still unserved. If the accused is found negative for drug use/dependency, then he/she will be released on time served, otherwise, he/she will serve his/her sentence in jail minus the counselling period at rehabilitation center.

4. As a rule, plea bargaining requires the mutual agreement of the parties and remains subject to the approval of the court. Regardless of the mutual agreement of the parties, the acceptance of the offer to plead guilty to a lesser offense is not demandable by the accused as a matter of right but is a matter addressed entirely to the sound discretion of the court.

a. Though the prosecution and the defense may agree to enter into a plea bargain, it does not follow that the courts will automatically approve the proposal. Judges must still exercise sound discretion in granting or denying plea bargaining, taking into account the relevant circumstances, including the character of the accused.

5. The court shall not allow plea bargaining if the objection to the plea bargaining is valid and supported by evidence to the effect that:

a. the offender is a recidivist, habitual offender, known in the community as a drug addict and a troublemaker, has undergone rehabilitation but had a relapse, or has been charged many times; or

b. when the evidence of guilt is strong.

6. Plea bargaining in drugs cases shall not be allowed when the proposed plea bargain does not conform to the Court-issued Plea Bargaining Framework in Drugs Cases.

7. Judges may overrule the objection of the prosecution if it is based solely on the ground that the accused's plea bargaining proposal is inconsistent with the acceptable plea bargain under any internal rules or guidelines of the DOJ, though in accordance with the plea bargaining framework issued by the Court, if any.

8. If the prosecution objects to the accused's plea bargaining proposal due to the circumstances enumerated in item no. 5, the trial court is mandated to hear the prosecution's objection and rule on the merits thereof. If the trial court finds the objection meritorious, it shall order the continuation of the criminal proceedings.

9. If an accused applies for probation in offenses punishable under RA No. 9165, other than for illegal drug trafficking or pushing under Section 5 in relation to Section 24 thereof. then the law on probation shall apply.

THE BASON RULING; CLARIFYING THE MONTIERRO GUIDELINES

More recently, in 2023, the Supreme Court addressed some of the issues in the Montierro Guidelines in the case of Bason vs. People (G.R. No. 262664, October 3, 2023). In this case, Manuel L. Bason (“Bason”) was charged with violation of Sections 5 (Sale of Dangerous Drugs) and 11 (Possession of Dangerous Drugs) of R.A. 9165.

Upon arraignment, Bason entered pleas of “Not Guilty”, but later backtracked and pleaded “Guilty” to two counts of violation of Section 12 (Possession of Drug Paraphernalia). The Office of the City Prosecutor of Roxas City opposed the plea, insisting that it has strong evidence against Bason and it already rested its case. The prosecutor insisted that Bason can only plea guilty from Section 5 to Section 11 in accordance with DOJ Circular No. 027. Additionally, the prosecution also questioned the approval of the plea over the its objection.

The RTC granted Bason’s plea bargaining proposal and convicted him for two (2) counts of violation of Section 12 of R.A. 9165.

The OSG assailed the RTC Decision before the Court of Appeals for which the latter granted, rendering Bason’s plea bargain proposal void. This prompted Bason to elevate the matter to the Supreme Court, arguing that the RTC did not commit any error in approving his plea bargaining proposal over the objection of the prosecutor.

The Supreme Court ruled in favor of Bason.

The Court held that the approval of the accused's plea of guilty to a lesser offense is ultimately subject to the sound discretion of the court as its discretion to act on a plea bargaining proposal is independent from the requirement of mutual agreement of the parties.

“Plea bargaining in drug cases require the mutual agreement of the parties but the approval is subject to the sound discretion of the court. If a plea bargaining proposal is objected to by the prosecution based solely on the ground that the accused's proposal is inconsistent with the acceptable plea bargaining proposal under any internal rules or guidelines of the DOJ, the trial court may overrule the objection after determining that the plea bargaining proposal circumscribes to the Court-issued framework on the acceptable plea bargains and by the evidence and circumstances of each case.”

The Court noted the instances of valid objections that may be posed by the prosecution. These objections, however, must be supported by evidence in order for the trial court to sustain them:

“However, when the objection of the prosecution to the plea bargaining proposal is valid and supported by evidence-to the effect that (1) the accused is a recidivist, habitual offender, known in the community as a drug addict and a troublemaker, has undergone rehabilitation but had a relapse, or has been charged many times, or (2) the evidence of guilt is strong-the trial court is mandated to hear the prosecution's objection and rule on the merits thereof.”

The Court upheld the RTC’s decision to grant the plea bargaining proposal because the trial judge meticulously examined the evidence of the prosecution and found lapses in the chain of custody of the drugs in question.

“Where the accused moved to plead guilty to a lesser offense after the prosecution rested its case, the trial court can rule on its propriety after assiduously studying the prosecution's evidence on record. The trial court's acceptance of the defendant's change of plea only becomes proper and regular if its ruling discloses the strength or weakness of the prosecution's evidence.”

Probably the highlight of the Decision is the point where the Supreme Court clarified the relevance of a drug dependency test after the plea bargaining proposal has been approved by the trial court. The Court ruled that a drug dependency test is not a pre-condition to the approval of a plea bargaining proposal. Under the Montierro Guidelines, it is clearly stated there that a drug dependency test is to be conducted only after the approval of the plea bargaining proposal.

“A closer reading of A.M. No. 18-03-16-SC suggests that a drug dependency test is not a pre-requisite for plea bargaining; in fact, it is to be conducted only after the approval of the plea bargaining proposal. To make a drug dependency test a requisite for the approval of a plea bargaining runs counter with the purpose for which plea bargaining was adopted in our jurisdiction.”

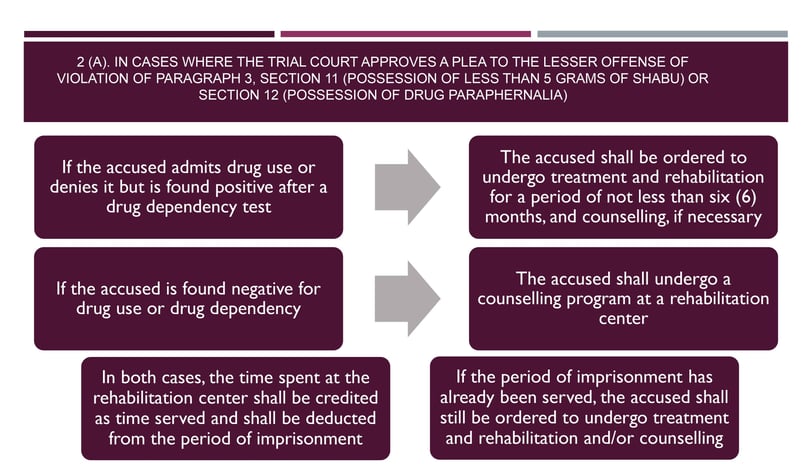

Finally, the Court rendered the clarificatory guidelines to support the Montierro Guidelines:

THE DISSENTING OPINION OF JUSTICE LAZARO-JAVIER

Even after the Supreme Court has settled some of the issues besetting the Montierro Guidelines, there remains much to iron out from these rules. At least, that is the opinion of Associate Justice Amy Lazaro-Javier, one of the current and esteemed members of the Supreme Court.

In her Opinion to the Montierro Guidelines, Justice Lazaro-Javier asserted that some of the provisions in the Guidelines are unconstitutional. Particularly, Item Nos. 5 and 6 of the Guidelines apparently diminishes (or at least modifies) the DOJ’s prosecutorial discretion. In the magistrate's view, these items are impeding the DOJ's substantive right to prosecute criminal charges which includes a vast range of activities, including the choice of who to charge, the decision to proceed or not to proceed with the prosecution, and the withdrawal or dismissal of charges. Justice Lazaro-Javier noted that the prerogative to proceed with the prosecution inherently covers the decision to plea bargain with the accused or not at all.

Additionally, Justice Lazaro-Javier found these items unacceptable even under the guise of the rule-making powers of the Supreme Court. According to her, such power can only operate under the proscription that the promulgation or amendment of rules must not diminish, increase or modify substantive rights. Through the mind of Justice Lazaro-Javier, prosecutorial discretion is considered a substantive right of the DOJ as it is inherently bestowed by no less than the Constitution.

Another compelling argument in Justice Lazaro-Javier’s Opinion is her criticism on Item No. 1 of the Montierro Guidelines which requires the accused to start plea bargaining with a written motion to the trial court. I would agree to this contention. Any practicing lawyer (especially defense lawyers) will probably scratch their heads upon reading this because of the potential exposure it could lay to their clients.

It must be underscored that plea bargaining deals in normal circumstances, or outside of drug cases for that matter, are practically conducted privately between the counsel for the accused and the prosecutor in charge of the case. It is typically done off the record; very rarely, does it go outside the negotiation table between the two (2) parties. More importantly, the details of the plea bargaining process must certainly not reach the ears of the presiding judge for fear of compromising his impartiality, unless it is already final and acceptable to both parties.

One can argue that Section 28, Rule 130 of the 2019 Amendments to the Rules on Evidence provides a safe haven for the accused whenever he plea bargains with the prosecution, thus:

“Section 28. Offer of compromise not admissible. – xxx

xxx

A plea of guilty later withdrawn or an unaccepted offer of a plea of guilty to a lesser offense is not admissible in evidence against the accused who made the plea or offer. Neither is any statement made in the course of plea bargaining with the prosecution, which does not result in a plea of guilty or which results in a plea of guilty later withdrawn, admissible.”

According to the quoted rule, the details threshed out during the course of the plea bargaining between the prosecution and the accused is inadmissible in evidence. However, the practical effects of a written motion to plea bargain is nevertheless undesirable for the accused. Here's why: If the plea bargaining fails, the accused has no choice but to proceed to trial before a judge that has firmly grasped the weakness of the case for the accused. This is especially true in instances where the judge denies the plea bargaining on the ground that the evidence of the prosecution is indeed strong. To recall, such a ground is one of the requirements of a valid objection to a plea bargaining proposal under Item No. 5(b) of the Montierro Guidelines.

The ramifications would be dire for the accused. Despite his earnest efforts to plea bargain so he can take a reduced sentence and proceed with its service, he will be facing a lopsided trial as the judge has probably pre-judged the outcome, making his conviction for a heavy sentence all the more certain. Surely, this might not be the intention of the Supreme Court in making this rule.

If you are thinking of moving for the inhibition of the judge who denied the motion to plea bargain and hope for the re-raffling of the case to another judge then think twice because that might not practically work out for the best. Since the plea bargaining proposal is initiated via a written motion, the filing of such motion puts the said proposal on record, opening the plea bargaining proceedings to the public. The re-raffling of the case will also result in the turnover of the records that contain the motion to allow a plea bargain and the corresponding denial of the previous trial court that handled the motion to the next presiding judge, and the next, and so forth. In effect, the impartiality of the judge who takes over the case will also be pervaded by the findings of the previous judge. With this, the situation of the accused would more or less be the same as in the last sala.

In line with Justice Lazaro-Javier's Opinion, the ending scenarios of a written motion has more of a calamitous pay off to the accused than what it’s worth. It would be very difficult for the accused to be afforded a fair trial moving forward in cases where his plea bargaining proposal is denied by the court, making the option to plea bargain in drug cases very unattractive to defense lawyers.

Wrapping this up, the ruling in Estepano Jr., allowing plea bargaining in drug cases certainly proves to be a friendly remedial measure to the drugs court’s docket management. The Montierro Guidelines on Plea Bargaining in Drug Cases is a welcome development to practicing lawyers and courts alike, considering the expediency and practicality of the process, a win-win scenario for everybody. The Bason clarificatory ruling ironed out some of the issues in the Montierro Guidelines, but there are still left to be improved as observed by Justice Lazaro-Javier. Although it may not be perfect, it seldom is when it comes to rule-making. Still, progress is paramount in the improvement of judicial economy and administration in drug cases. It is imperative that we persistently strive for continued improvement in these aspects for the advancement of our judicial system.